South Pennine magical realism

Saddleworth where I am from is in many ways a place-in-between. The parish is situated on the historical borderline of Lancashire and Yorkshire’s West Riding, and the question of whether it lies in one or the other is like a running joke one returns to compulsively as an excuse to touch on something actually very serious indeed. To the west are Oldham and Ashton, birthplaces of mechanised cotton spinning synonymous with the dizzying accumulation and misery of the Industrial Revolution; travelling east, the A62 takes you over Standedge escarpment, vast and inhospitable peat bog wilderness and moorland. The distance from one frontier to the other is, at points, less than four miles.

Needless to say, the varied landscape of the South Pennines has contradictory qualities. The towns of north-east Manchester are often described as among the most impoverished and unsightly parts of the whole country. Bucolic Saddleworth, a ten-minute drive away, is widely renowned for its natural beauty, yet local history is awash with violence, grievances, ghosts and the unexplained. When explaining to people of certain generations where we lived, Mum would always place us “between Manchester and Leeds” – not for Saddleworth’s obscurity, but to dodge reference to the infamous murders of the 1960s. The last time Saddleworth appeared in the national news was as the site of the worst wildfire in British history.

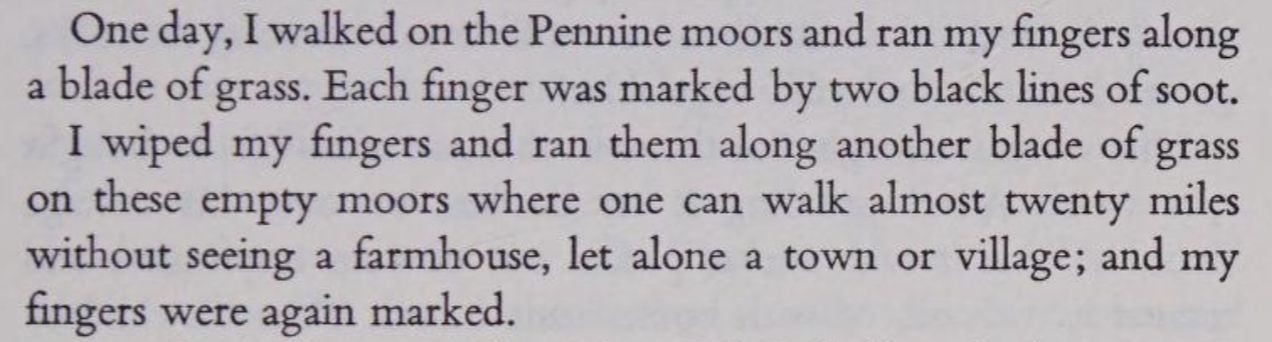

Moors; "contradictory qualities". Those who love the moors the most are themselves most likely to underscore their bleakness and emptiness. Part of their strange, romantic pull comes from this perceived hostile indifference to life, this non-humanity that seems to stand outside of civilisation and time itself. This is, of course, a fiction, and under the right circumstances (usually those of catastrophe) the marks of human activity are uncovered. A case study of the 2018 wildfire observed that Saddleworth peat contains “elevated heavy metal levels due to a long legacy of airborne deposition from heavy industry in this region”. In addition to this, one of the causes of the fire’s rapidity was not just the exceptionally dry summer weather, but particular methods of land treatment used by commercial grouse shooters, where wet bog is drained and low-lying heather is maintained to make the birds easier to breed, spot and kill. While vegetation quickly recovered after the fire, the most irrecuperable loss was the carbon stored over millions of years in the peat, which accounted for much of the 36,720 tonnes of C thrown into the atmosphere by the fire (equivalent to the annual emissions of around 86,000 passenger cars). Ultimately, it wasn’t the fast-burning heather that made the fire so difficult to extinguish, but this hidden lit peat, which would slowly smoulder out of sight before flames burst to the surface, reigniting the blaze.

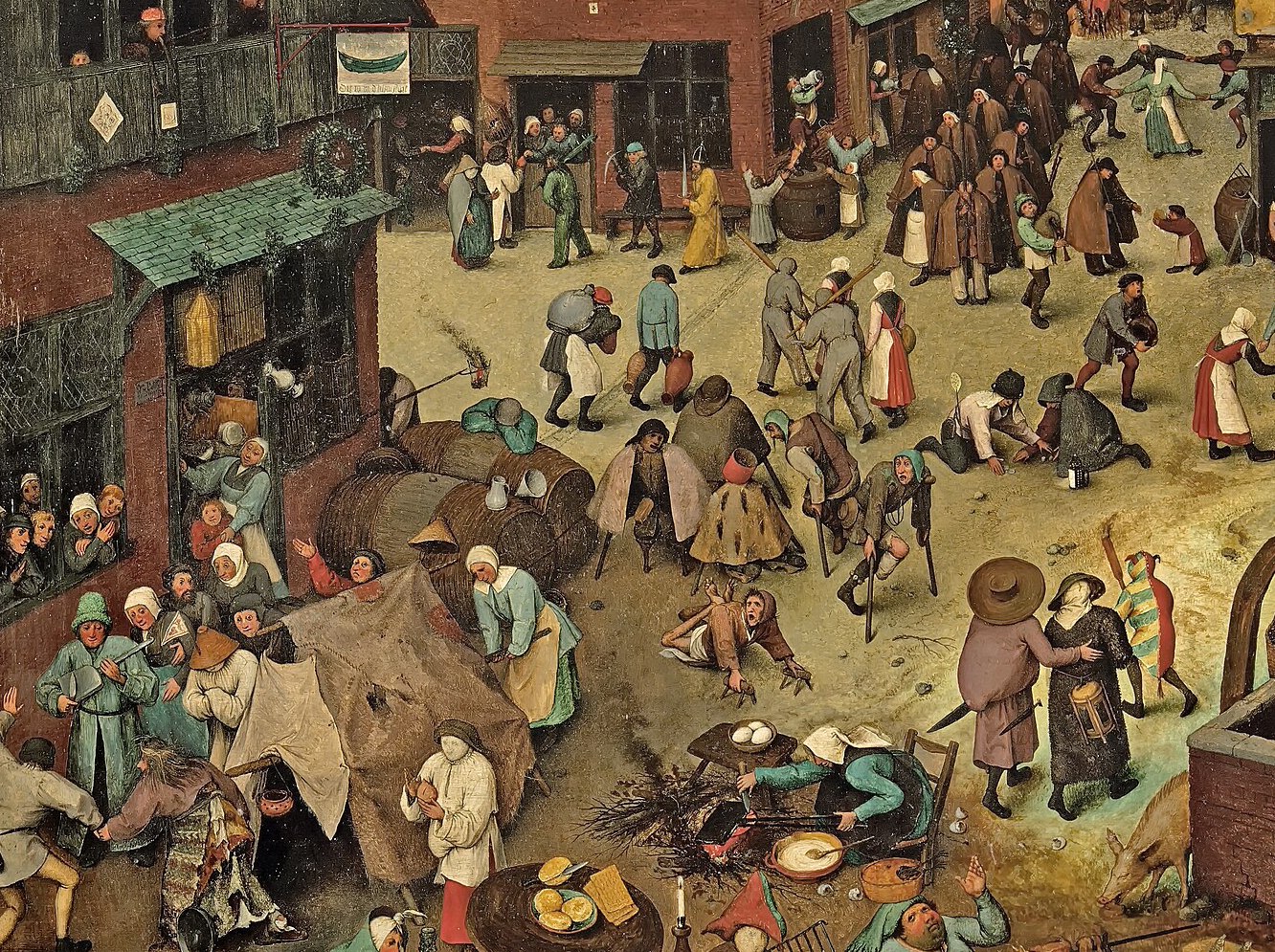

Writers of the South Pennines have made much of the region's dissonances, and the ways in which its industrial, pastoral and wild aspects impinge on and complicate one another. Saddleworth's Ammon Wrigley (1861-1946), poet and avid grouse-shooter, wrote that "our parish has two ends — one composed of heather, sweet winds, and old-fashioned farm houses; the other composed of cotton fly, wheel grease, and soot", and used the peculiar phrase "industrial villages" to describe settlements which, while rural in appearance and custom, were at the same time active participants in the North-West's cotton and textile boom. More than half a century later, Glyn Hughes wrote (not without affection) that he felt it “more than an arbitrary accident that when pre-industrial artists painted their images of hell — I am thinking of Bosch and of Brueghel — their flaming wastes amongst dark, amorphous, threatening forms bear the most striking resemblances to the industrial valleys of Lancashire and West Yorkshire, Huddersfield, Colne, Rochdale, Burnley, Oldham, that were to make the painters’ horrifying visions into palpable realities.” Hughes was originally from Cheshire but spent most of his life in the South Pennines, nearly a decade of it in Saddleworth, which in his Millstone Grit he described as a place “of violent conflicts that were, perhaps, as much products of that violent weather over the denuded uplands, as they were products of social forces.” Here ‘social forces’ means many things – not just what we would now call Saddleworth’s gentrification (described in Hughes’ book as the conflict between ‘natives’ and ‘comers-in’), but the nostalgic stasis of its older residents, descendants of Luddites, Chartists and Suffragettes now wedded to the easy comfort of old traditions.

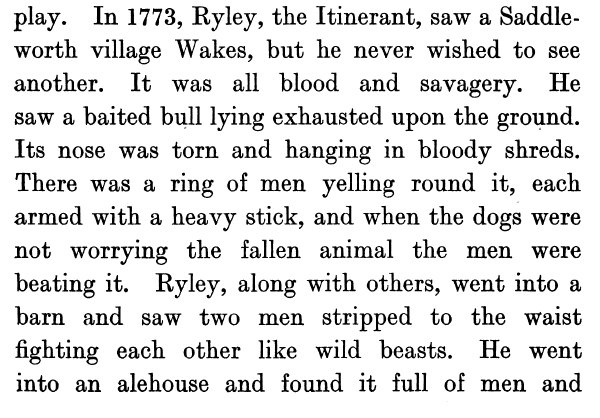

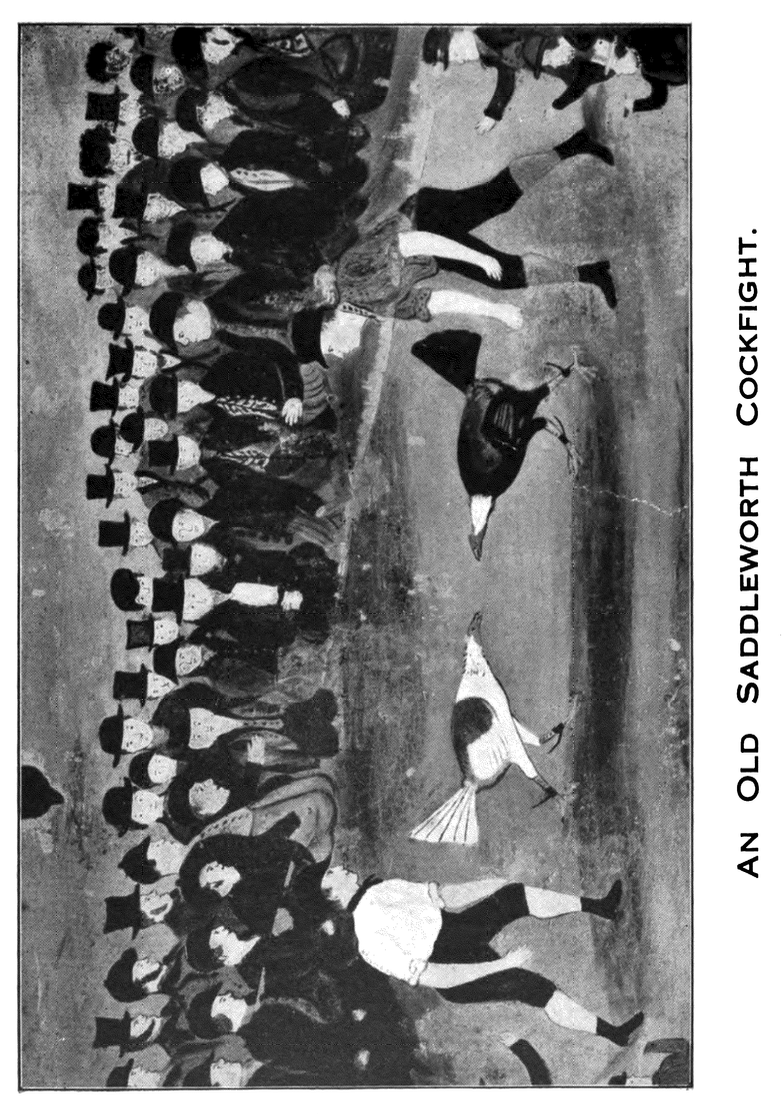

This includes the work of writers like Wrigley – Hughes recalls a Saddleworth landlord reciting verse after verse of Wrigley’s poetry from memory, misty-eyed paeans which Hughes gently criticises, not unreasonably, as “mechanical, didactic and sentimental”: “Home to old Saddleworth, home once more, / How my heart is stirred to its innermost core; / For I’ve been roaming and it’s a joy to go; / Up the hillside lane by the fields I know / Home to the hamlet where my own folks bide, / To the old armchair by the hearthstone side…” (and so on). Hughes is kinder about Wrigley’s prose, which paints a funnier, broader and more complex picture of Saddleworth’s people and history. Like Hughes, Wrigley is deeply nostalgic for and fascinated by histories of violence. Saddleworthians brawl, drink large quantities of ale, and mortify foreigners.

As one often finds in travelogues, both authors have a tendency for nostalgia and mystification. Both are also heavily preoccupied with Saddleworth's perceived physical and moral decline. Wrigley is the more conservative figure, lamenting the slow dying-off of old-time village characters and architectural and social transformation. "Any lad over eight years of age", he observes sardonically, "can give you the age, weight, and career of a thousand footballers with remarkable ease and certainty. This is one of the dispensations under the law of progress." Hughes, picking up the mantle in the 1970s, sneaks in a couple of jabs at New Towns alongside his above-mentioned melancholy for the decline in working-class Radical autodidacticism. Both authors, particularly Hughes in the revised edition of Millstone Grit, have a slightly irritating habit of insisting on the down-to-earth simplicity of their subjects, even when both are well-acquainted with, and discuss at length, the idiosyncrasies and metaphysical interests of "the dalesmen". This of course chimes with the broadly-held view that it is in a northerner's nature to mind their own business and stick to their ways -- notwithstanding the fact that their own books contradict this, or that the stereotype of generally adhering to one's existing socio-cultural norms and practices could well be applied to most of Earth's population, cosmopolitan Islingtonites among them.