Three Histories of Men in the Music of Kiran Leonard (c. 1970; 2000; 2014-17)

the events of ‘river in the valley’ are very much a true story, related to me by a friend about his university experiences some 15/20 years prior. said friend really did walk into a bar near to campus (i think during freshers' week) and proceed to a back room where he came across a coterie of rugby lads in the process of ’initiating’ a new member to their team. this was being done via no doubt ancient ritual: one (1) team member, lager in hand — in the song, i say it is a ‘can of pilsner’, but this is me taking poetic liberties, and in hindsight given the circumstance it was much more likely a pint glass — was situated beside a fellow veteran (2), and they were both stood on top of a table surrounded by their teammates. team member (2) had his bare arse out; i think (1) was fully clothed, or at least had no discernible reason not to be (as you will see, the exposed arse of (2) was an absolute necessity). the new member (0) was laid out supine on the table, mouth opened, and his head positioned between (2)’s ankles and with (1) probably stood over (0)’s hips. for the initiation ritual to work, i am sure that (2) and (0) had to be positioned with upmost accuracy. my friend sees (1) begin to pour his lager over (2)’s shoulders. as the trail of liquid runs down his back, said friend realises that the path of the pilsner has been determined perfectly so that it might pass straight through the crack of the arse and into the wide and welcoming gob of newbie, an apparently willing participant. as the first drops spatter his lips the room erupts. said friend says he has never understood the significance of what he saw — why him? — and in writing this song i too was unable to reach a satisfying conclusion. maybe this is presumptuous of me but it’s such a vivid and surreal recollection that i can’t help but think there is a kernel of truth in it somewhere. the lengths to which this poor subject went so that he could feel rooted, to grasp on to a sense of belonging

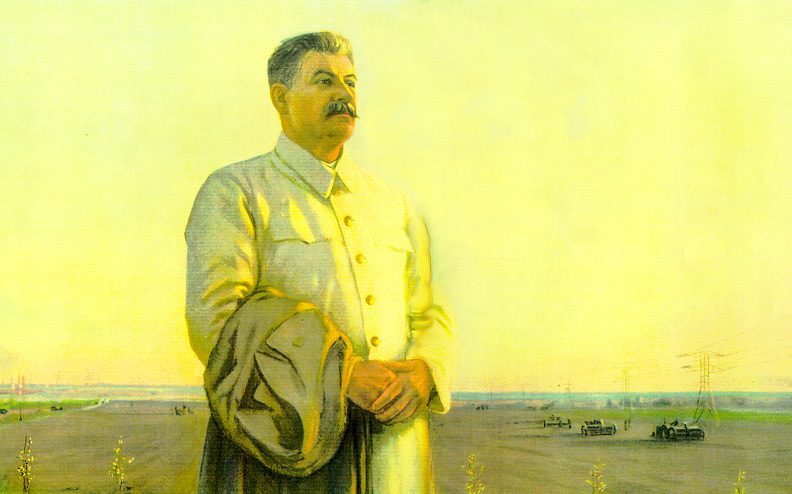

“A boy, in his attempt to gain an elusive masculine identification, often comes to define this masculinity largely in negative terms, as that which is not feminine or involved with women. There is an internal and external aspect to this. Internally, the boy tries to reject his mother and deny his attachment to her and the strong dependence upon her that he still feels. He also tries to deny the deep personal identification with her that he has developed during his early years. He does this by repressing whatever he takes to be feminine inside himself, and, importantly, by denigrating and devaluing whatever he considers to be feminine in the outside world.”

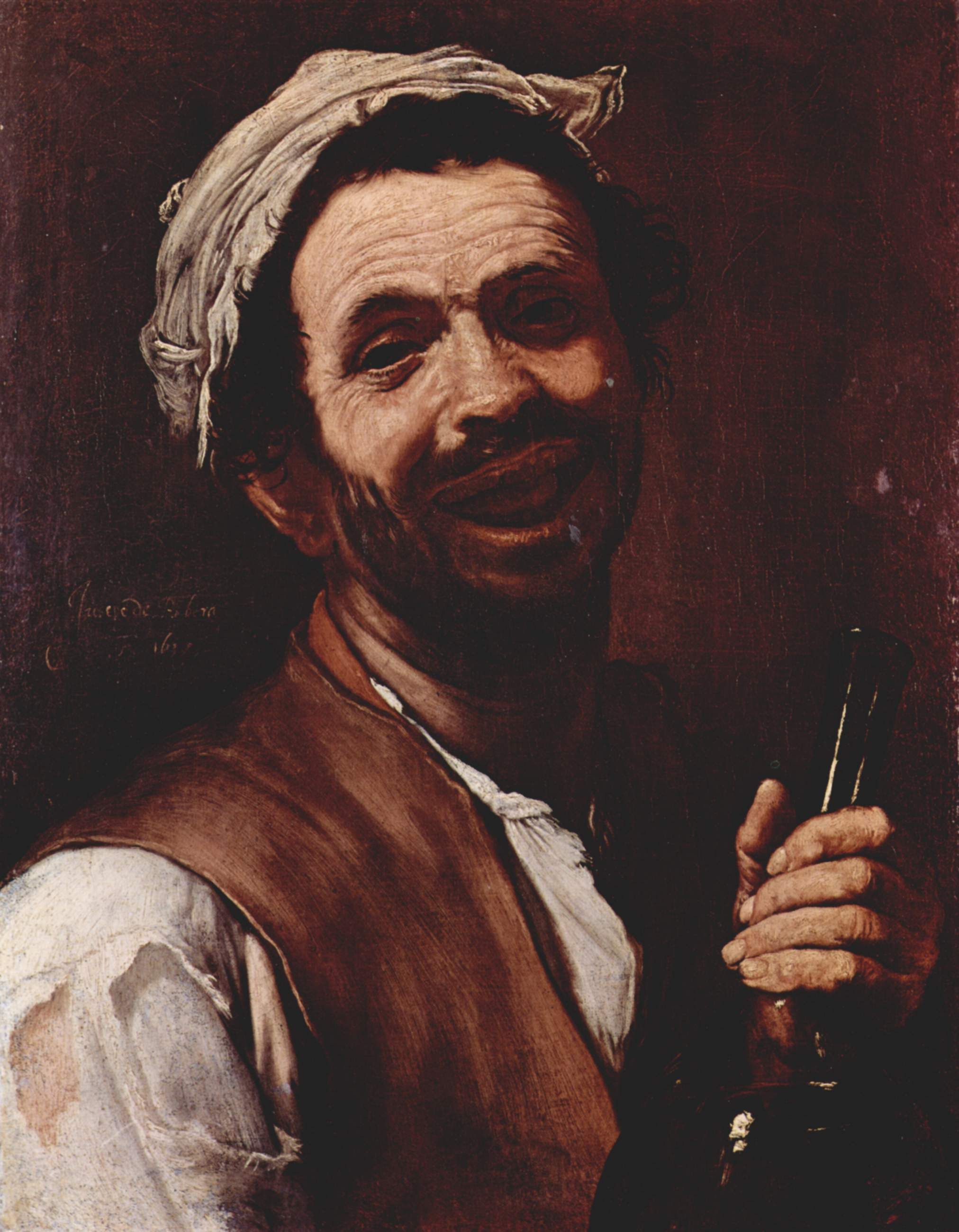

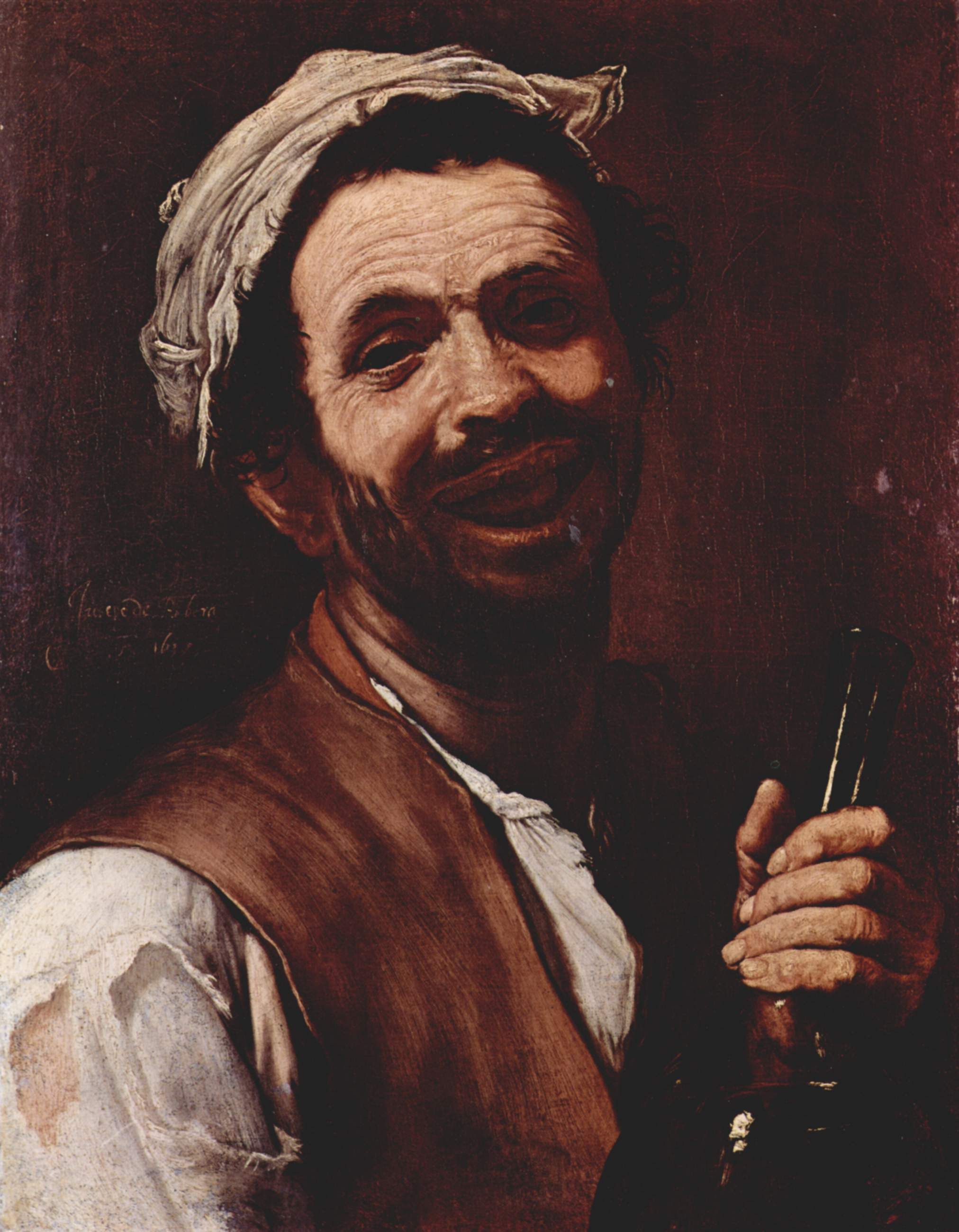

He told me a story once about Thurnscoe, near to where he grew up. The story was that there was this pub there—he would often go to the folk club there—whose landlord was a bit of a notorious town character. Partly on account of the fact that he was hardly the pub landlord at all, because his wife was mostly left to manage all that, on account of his habit of heavy drinking. And he was a serious heavy drinker, a bottle-a-day whisky drinker. Every day, he would rise early, crack open a bottle, and that was him set. You could find him any given afternoon, just about stood, propped against the bar with his whisky and a funny grin on his face. He always had a grin on his face but it was one of those funny, menacing grins. He had a troubled and somewhat distant look about him. And he’d lurk about his pub and grin and drink his whisky, and sometimes he’d talk. Certain days he was more talkative than others. But if the mood took him he’d talk incessantly, until long after closing, veering from high-spirited tall tales to a sort of dour, non-descript nostalgia, the kind committed drunks are prone to.

And more often still he would talk about when he was a shipbuilder. Now this was a long time ago. He’d either retired or been laid off, he would tell different versions of the same story. And he’d been a pub landlord for much longer, probably, than he’d ever been a shipbuilder. But he always spoke very fondly of his old job; it was one of the few subjects he could hold counsel on with any lucidity. And the strangest thing was he’d even started building a ship of his own, in his back garden. Upwards of a decade, slowly accruing materials from round town, and building this boat, this in a town in South Yorkshire which must be some ninety miles from the nearest coastline. He wasn’t at it every day, like he was with his drinking, but it seemed a project he would return to consistently. And year on year, the project grew in size and ambition. Its tilted hull stretched in a complete diagonal arc from back door to far wall, sat like a fishing vessel run aground, its bow splintering the remains of a garden shed long since harvested for spare parts. And the landlord and his wife lived in a terraced house, one with the garden hemmed in on all sides. If he’d ever figured his creation sea-worthy, they’d surely have needed a crane to lift it out onto the street.

Nobody ever asked him if he’d thought about how to overcome this difficulty, or where he planned to go with his boat whenever it got finished. I think more than anything they found the project impressive, even quite noble, in and of itself. Or perhaps they were worried about offending him. So much else in his life didn’t make sense, or wasn’t fit to comment on. The whole endeavour seemed to go beyond ‘why’; the question of ‘why’ never came into it. In the end, they’re not sure how he died or what happened to his boat. The pub is now derelict.