FAUT-IL BRÛLER FZ?

I’LL STOP SHORT OF SAYING HE WAS A GOD -- even at the absolute height of my obsession with FZ (c. 2008-2011, between the ages of 13 and 15) there was music of his that tested my patience / sense of good taste -- there were other artists and modes of expression that interested me, I never feared him -- but although I return to his records very infrequently, and his work now seems so far removed from what energises me about making and experiencing art that it is as if I have renounced him, the grammar of those records is burned so indelibly into my brain that his influence somehow touches every piece of work I set out towards, in the way that sacred texts and their teachings continue to exert an influence on non-believers long after they have left the creeds of their childhoods behind.

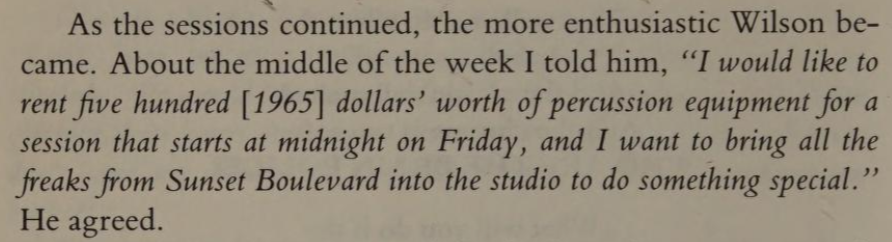

FZ’s contributions to the LP form are as revolutionary as Godard’s to film, and similar in their playfulness with the impossible spaces and timeframes their respective media can create -- FZ calls them “imaginary rooms” [RFZB 158] -- tho the key is not just the formation of these rooms but how he moves between them -- at his best the records are more like falling through the successive storeys of a tall building, R&B to Webern to musique concrète to dinner theatre -- from studio to live, coast-to-coast in a ‘split’ second, sometimes seamlessly, but mostly drawing attention to an imperfect convergence -- record scratch, snork --

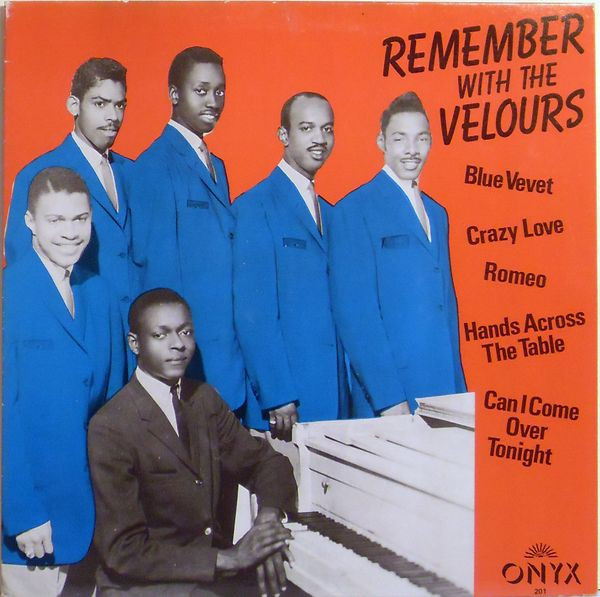

It has often been remarked that Godard and his contemporaries were the first generation of filmmakers who were themselves film fanatics; whose self-aware experiments placed their work in a unique dialogue with other films, and whose plots and forms drew attention to themselves as films / products of its history. This is another point of similarity with FZ, who must have been among the first composers to have educated themselves almost exclusively listening to mail-order LPs in his bedroom, and not in the nightclub or the conservatoire. FZ was almost entirely self-taught (like the cinéastes), detested academics, and was dismissive of his early experiences of live music, both as performer and spectator. All of his formative influences -- Varèse (to whom he spoke once over the phone after tracking him down in a New York directory, but never met in person), Charles Ives, Johnny “Guitar Watson”, Lord Buckley -- he encountered on record or on the radio; perhaps the primary source for his nouvelle vague-like elasticity with form, also driven by the desire to collapse arbitrary distinctions of style and intellectual worthiness--

JLG/FZ: both also early builders of similar, metatextual languages sustained over several decades; both combined high and lowbrow materials but with none of that wry, postmodern superficiality (well, maybe JLG did a bit of that in the early days); both had idiosyncratic, sardonic conceptions of contemporary culture, society and politics, which they conveyed through artefacts collected and recontextualised with a critical distance (“Louie Louie”, Bogie in À Bout de Souffle, bottomless super-impositions of sound and image, numerous items of sleaze, quotations, parodies). Although ofc it’s hard to imagine an author FZ would hold in lower esteem than the bookish, self-absorbed, frequently didactic obscurantist JLG, both were, in their own way, materialists, and often of trash (Ben Watson, author of the best book on FZ by a country mile, consistently stresses the nature of FZ’s oeuvre as materialist and trash-based above all else)

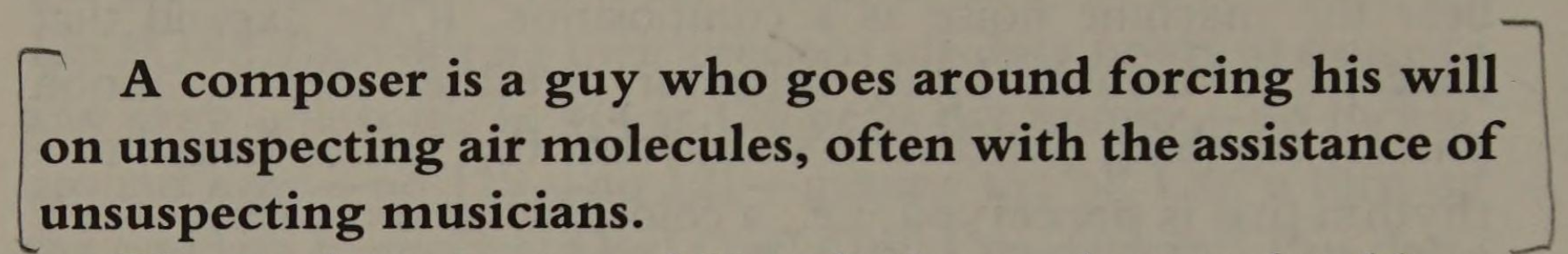

"MUSIC COMES FROM COMPOSERS--NOT MUSICIANS" (RFZB p174)

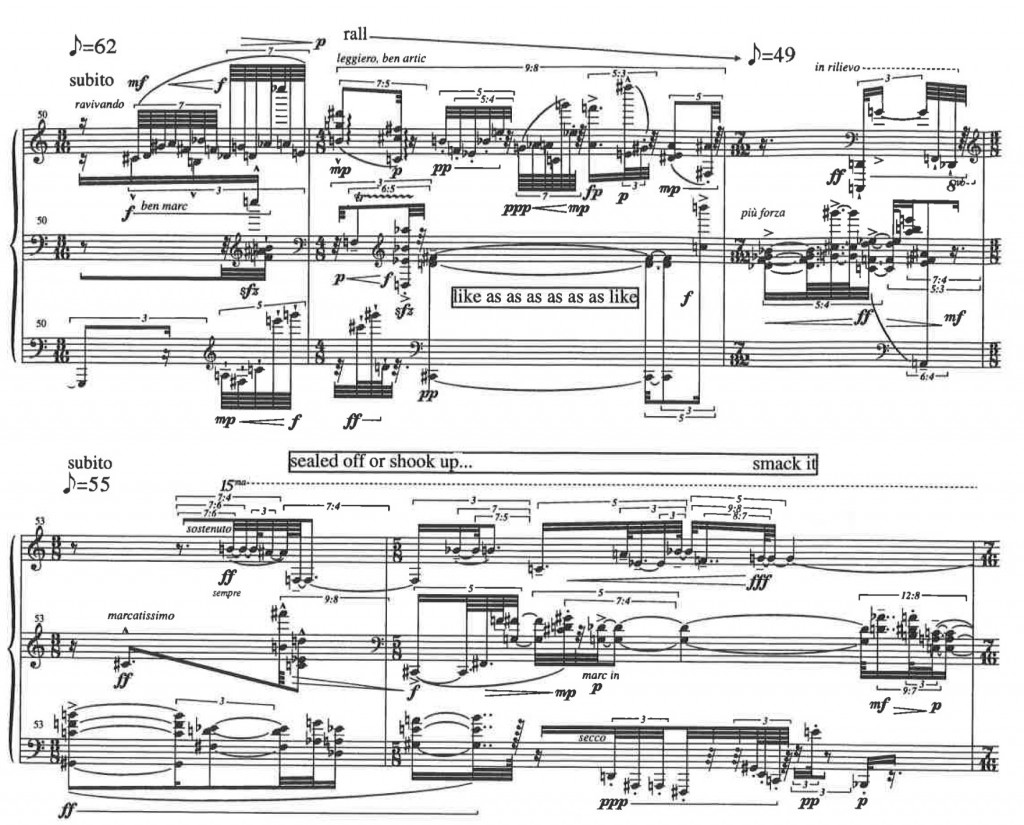

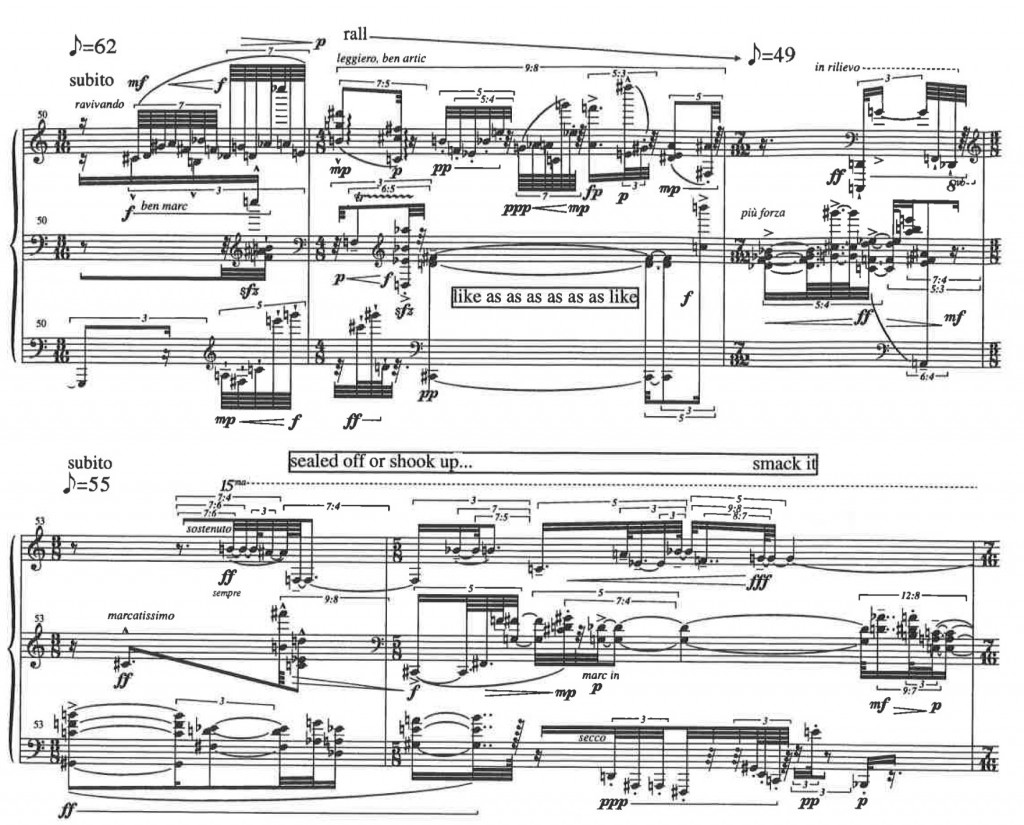

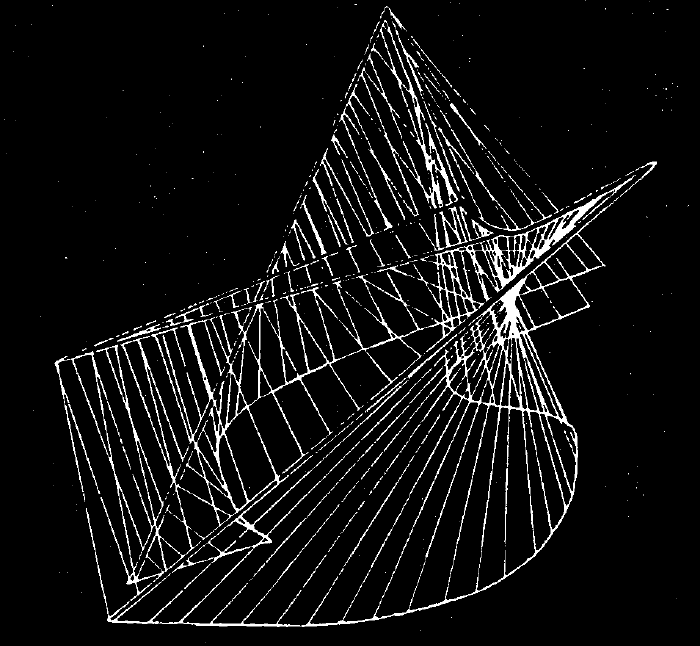

But I’m not sure if it is just the interviews: surely there’s a point (which to Watson’s credit he sort-of acknowledges, starting for him in the late 1970s) where that sense of intellectual superiority gets baked into the grammar itself -- especially when the CEO genuinely doesn’t need other voices (unlike how Beefheart, Mark Smith genuinely needed them), especially when the goal is maximum efficiency, maximum fidelity to a perfectly-ordered vision -- and so as other voices slowly disappear from the work, FZ seems to becomes even more certain of his brilliance, as if he wasn’t already certain enough (one of the virtues of JLG: he becomes less certain of himself and the value of his work the older he gets, and his work starts to reach even further outward as a consequence -- FZ instead moves inward towards greater precision, more tied up with accumulating details of himself -- think of our protagonists in the 80s: the difference between JLG's embrace of video technology to broaden and complicate his work and FZ's embrace of the Synclavier to do away with the weight of other people holding him back) -- and so doesn't the project/object just become another smug, intellectualised construct: still material, anti-text, anti-academia excepting technologies of science, but still a monument unto itself and its dizzying intricacies -- and again, to stress, this isn’t me renouncing FZ’s politics and confusing it with his music, I’m saying that the former audibly informs the shape of the latter, Frankfurtian readings of the significance of his tools for montage notwithstanding -- basically does there not come a point where FZ and eg Brian Ferneyhough are building the same kind of cerebral, hermetically-sealed universes by different methods, is that why the content of these records so often make me feel nothing even when their form continues to engage me

"how could i be such a fool?" (1966)

lumpy gravy (1967)

"what's the ugliest part of your body" from we're only in it for the money (1968)

theme from uncle meat (1969)

"holiday in berlin full blown" and "the little house i used to live in" from burnt weeny sandwich (1970)

"the nancy & mary music" from chunga's revenge (1970; favourite audience participation on FZ record)

overture and "dental hygiene dilemma" from 200 motels (1971)

all of the grand wazoo (1972)

"zomby woof" from over-nite sensation (1973; fave FZ solo)

"inca roads" (1975; for dave)

studio tan (1978)

"manx needs women" (1978?)

jazz from hell (1986; only synclavier FZ you need)

"ruth is sleeping", version on the yellow shark (1993)

back

site map