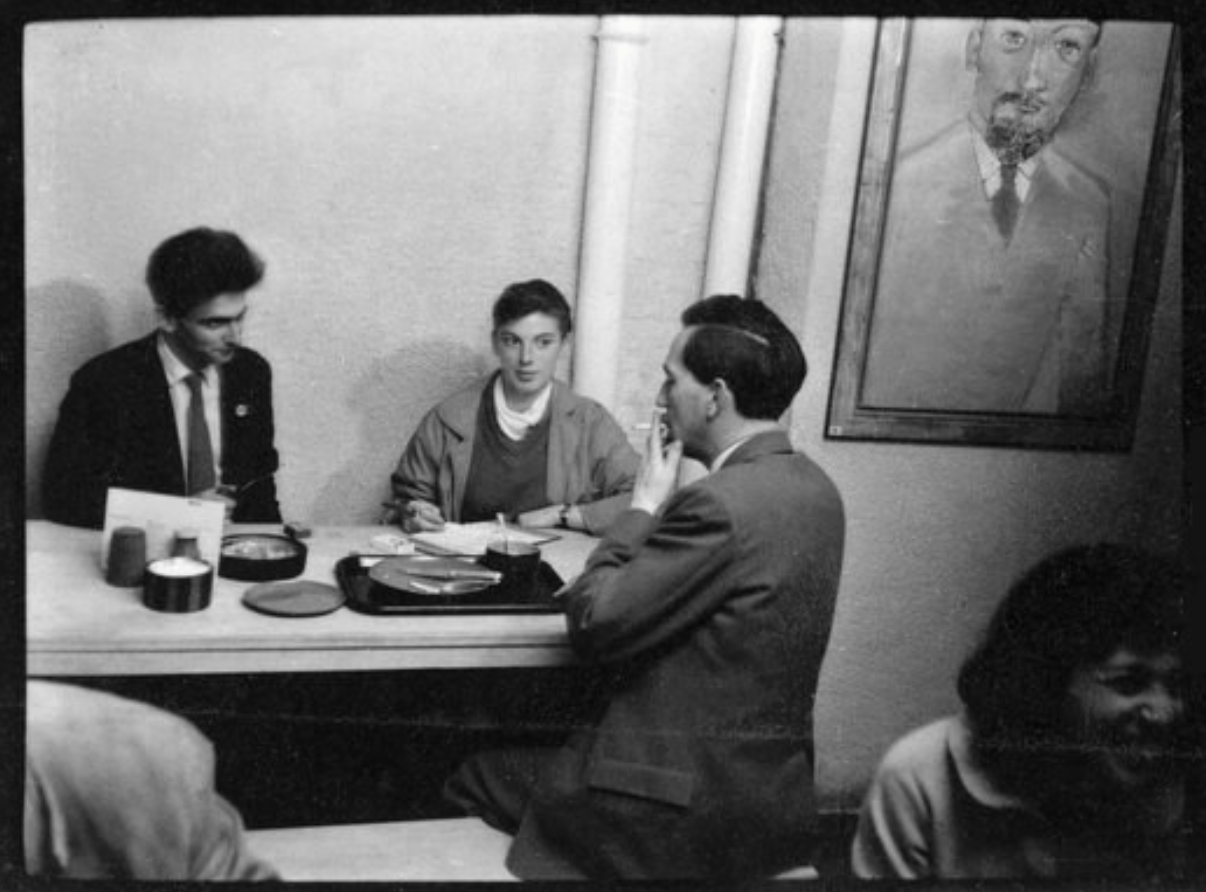

Dreaming. He speaks of writing as truth and speaks of it as dreaming. “Really what I do is to dream with my eyes wide open; […] to be paid for retreating into my private world, which is the one thing above all others which interests me.” His protagonists often experience moments of truth as if entering dream states adjacent to, and more real than, reality. The whole construction of Tom and Dick’s Vodi myth is in pursuit of such a state. In Room at the Top, just before Lampton sees the man with the beautiful girlfriend and Aston-Martin that sets him on the path for bigger and greater things, he has a premonition entering a café brought on by an attack of pins and needles: “the incident seemed, for the duration of that second, to jar my perceptions into a different focus. It was as if some barrier had been removed: everything seemed intensely real...”

We are starting all over again, again. There is always something on his periphery: a suppressed ambition, an unseen threat. It doesn’t help to try and speak its name it only grows. The moors have something to do with it in his novels. They are the border of every town and the horizon of every street. They are the bridge you cross to get from one place to another, and our desire’s territory. We go to the moors together for sex and return changed people. We should not go there at night because we might get lost.

But there was something else, not out there but inside of people. It was in him as well: the imperfections gnawing. Better imperfection, he would tell himself, than to agitate for change; better this than our common, individual pleasures falling from reach by our trying to improve our collective lot. In the documentary, he is happily pottering around the office he keeps for writing in town and the mood suddenly shifts. Periphery steps towards us. In a scene that is repeated in the Queen of a Distant Country, the novelist suddenly brandishes an arsenal of photographs from the Russian Civil War. Where have they come from and why does he have them? The photographs are of child refugees. If it was not already clear, the novelist is hysterically right-wing. “This is what the New Left want,” he says. “This is what the Communist party wants, this is what all the parlour revolutionaries want. A child screaming in unendurable pain and terror […] That is what happens when you say human nature is perfectable.” He shuffles his deck and faces a new photograph towards the camera. “Another group of refugee children – and what you’ll have to remember is this: that each one of these children once would have had a home, would have had a father and mother, would have lived in an atmosphere, no matter how poor they were, of love. And now they are adrift in a world without love, in a world where death is king.” His voice wavers, he has brought himself to tears. “Rather than have this happen to my own child or to anyone’s child I would do anything. When I say anything I mean anything. We shall not keep our freedom and keep our hands clean of blood. It cannot be done.” Eventually this monologue comes to a sudden end. Scene change. It is 1971 and we are in Surrey.

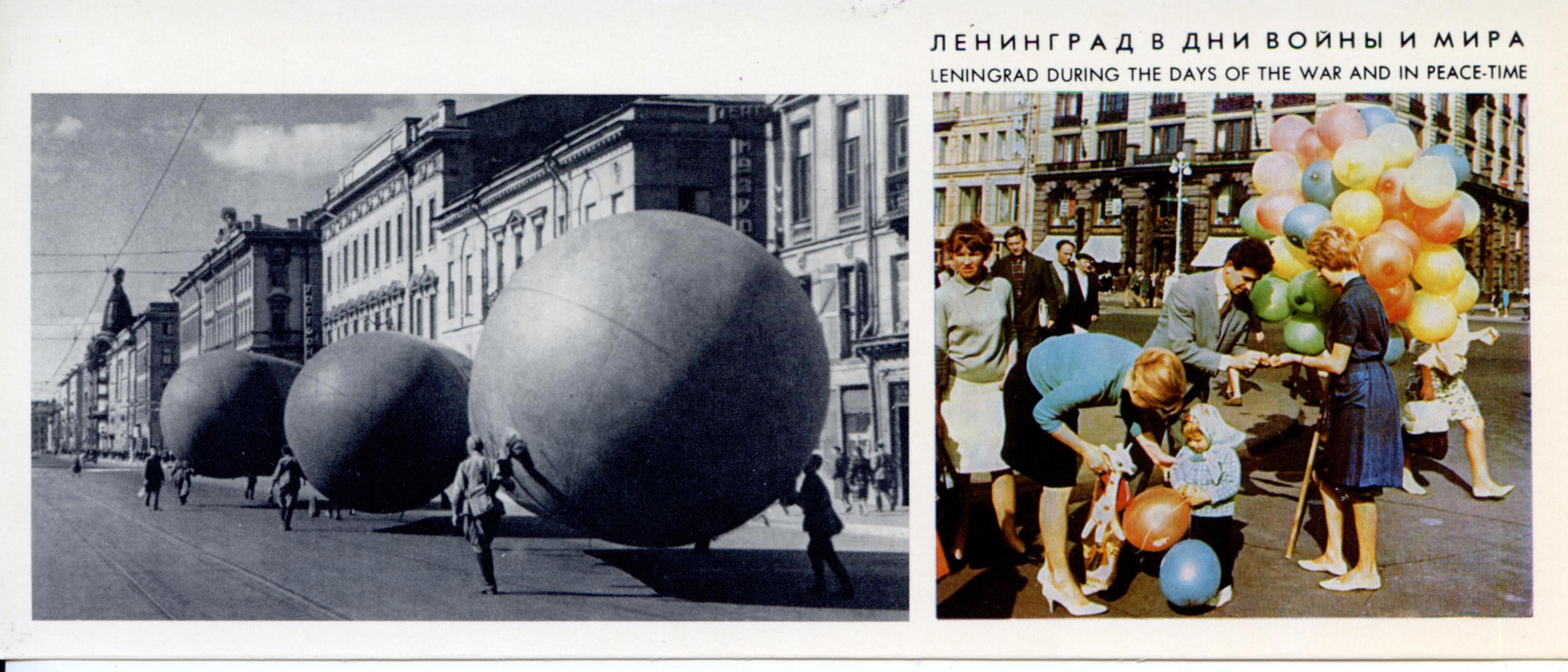

He is still trapped inside of the cage. Not long after this cathartic outburst, incredibly, he goes on to speak of Leningrad. He sits in his lounge with the lights off before a slide-show projection of photographs of the Peterhof Palace. “The difficulty,” he begins, “is that though I’m quite happy to accept the world as it is and English cities and towns and villages as they are, there’s a part of me which can’t help hankering after perfection. Perfection for me is only in Leningrad […] you recognise with reared reluctance that you have broken through into a magic world; in a way you have broken through into the story.

“Most of the time, one goes through life in this country, precisely because it’s so comfortable; precisely because it’s so settled; because we have had our freedom for so long and we have had law and order for so long; [...] you never think about history, you never think about the problems of power […] But I think of Leningrad and all that there is to be seen in it, and the feeling of helplessness grows. The splendour of it all.”

In an interview with the Yorkshire Post, his widow would later say that his personal and professional decline began after they moved to Woking in the mid-1960s. His drinking worsened. One day he told her he was seeing another woman; after he physically attacked her in their home, she left him. Then he lived in Hampstead and died of a perforated ulcer, fifteen years after making his film. Colin Wilson said, very gently, that he had died of ‘self-division.'

It’s because he’s still trapped in his cage in Small North: disoriented and paranoid, thinking he dreams of the truth. He ends the film by saying: “We take so much in this society; we have a duty to give something back. And we can only do this by fighting to preserve it, at the cost of our lives, if needs be […] For me, that society is England. I know the shapes and sounds and colours of its being. And the only doubt I have is a doubt about myself: that strange nostalgia for Leningrad. There is a part of me that hankers for grandeur, that relishes the salty taste of power, who craves to fill his eyes again with those great buildings under the steel grey sky. But there are worlds within us all which we had better not explore.”