Revision, 27/07/2020: Since I completed this article I have had two separate discussions where my interpretation of the Fátima visitations has been dismissed as confused or baseless. I spoke to one friend, a Portuguese-born academic, about the pastorinhos but did not mention that I had written this short essay on the subject a few months previously; they were very critical of my analysis of what happened, claimed there were inaccuracies in my knowledge of the event and cited their own extensive religious education in asserting this. Perhaps I had drank too much wine and confused myself in conversation: in any case, I have re-read my essay before publishing it here and am not aware of the presence of any factual errors (much of what I have to say about the event comes direct from the memoirs of Sister Lúcia, the eldest of the shepherd children). Another friend of mine, not familiar enough with the story of the pastorinhos to have such objections, instead found the insertion of Camus into the piece confusing and unjustified. I believe that both these criticisms are fair: perhaps I became too absorbed in the story of Fátima and the culture surrounding it to think laterally, and I confess that Camus' presence was motivated by a desire to tie the essay into promotion for an LP rather than for any purely intellectual reason. But I would say in my defence that this short essay is not a work of history or biography: primarily, it is an analysis of faith but also of power. I offer this somewhat selective (though not misleading or unwarranted) overview of events as a necessary provocation, given that any discussion of abuse of power seems entirely absent in the conversation surrounding the visitations, which shocked me given the numerous instances in which the children were clearly subjected to tragic and horrifying ordeals both before and after their encounters. As for Camus: yes, it is a bit contrived, but I think there are a few moments of interest which come from the cross-analysis of such different viewpoints. So make of it what you will.

***

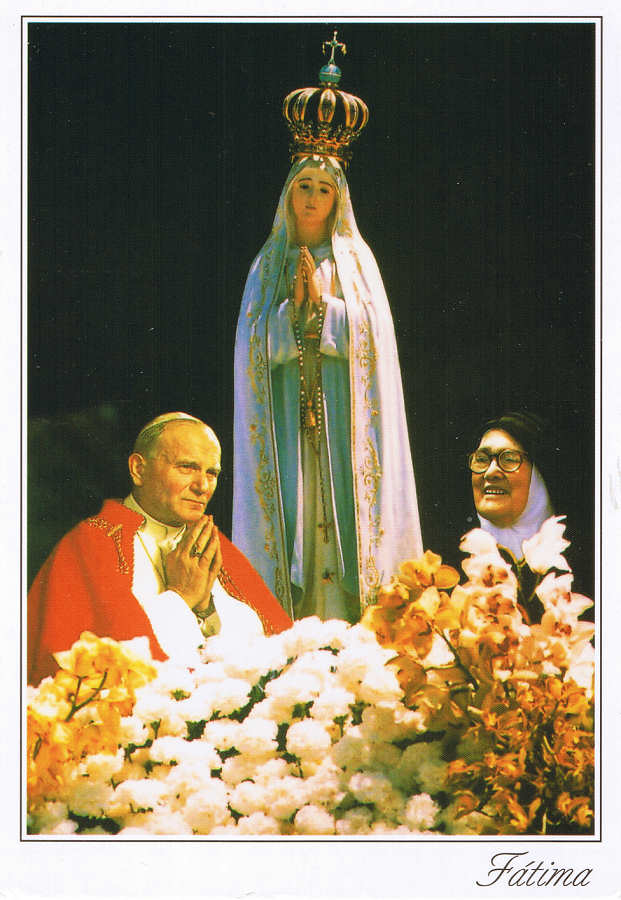

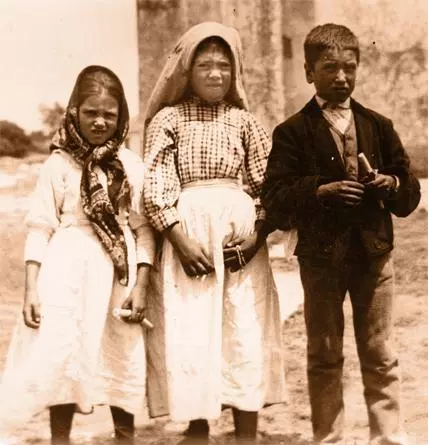

Lúcia, the eldest by just over a year, was the only one who spoke to her. Her cousin Jacinta could hear her; Francisco, her brother, could just about see her. She first came to them in a pasture owned by Lúcia's parents, the exact location of the apparition now marked by a glass-enclosed idol that stands before a small chapel. Today this modest building is but one part of a vast complex dominated by two separate places of worship, built to accommodate the four million pilgrims who travel here each year. A white strip runs from the far end of the site up towards the basilica, for those who wish to make the journey on their knees. And on the right-hand side of the Sanctuary, visitors unexpectedly come across a segment of the Berlin Wall, intended to stress a connection between the fall of communism and her request for the consecration of Russia. Beside it, a flagstone is engraved with a quotation in Portuguese from the man who donated the piece:

“Thank you, heavenly shepherd,

for guiding the people to freedom

with maternal kindness.”

-John Paul II, 12th May 1991, in Fátima

On the centenary of the first visitation, Pope Francis travelled to the Sanctuary of Fátima and led a large outdoor mass marking the official canonisation of Jacinta and Francisco de Jesus Marto. In his homily, delivered before a crowd of half a million people, he commended the “fidelity and ardor” with which they embraced the significance of their vision, emphasising the importance of nurturing the potential of children within the Church. The congregation listened in complete silence and with firm concentration. Later that afternoon, as Francis took a driven procession from the Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary and into the streets of town, thousands ran behind and alongside his motorcade, and openly wept, and cried out his name. He waved and beamed into the throes as he slowly disappeared from view, and was escorted to a nearby air base.

He often speaks of doubt and periods of uncertainty in his faith. Like so many before him, he teaches that doubt and its tribulations constitute the inevitable and necessary path to a subjective and deeper understanding of the spiritual: “Doubts which concern the faith, in a positive sense, are a sign that we want to deepen our knowledge of God, Jesus, and the mystery of His love for us”. In his Introduction to Christianity, his predecessor Benedict XVI proposed seeing the believer and non-believer as components of a dialectic, both caught between varying degrees of faith and doubt in their respective interpretations of the world; that, just as even the most devout Christian may struggle with what St. Thérèse of Lisieux called the “worst temptations of atheism”, the nonbeliever “is troubled by doubts about his unbelief, about the real totality of the world he has made up his mind to explain as a self-contained whole”. In other words, a sense of and deference to the unknowable is the natural disposition of all mankind. From all sides we pass by one another, invariably trapped, navigating the difficult in-betweens of our not knowing.

What Camus tried to do in response was make peace with this, and find reasoned, inherent freedom and value in an existence lacking any certain order or direction. Breaking from theologians as well as other existentialists, he chose to stop trying to make sense of the ontological void, and instead take its inscrutability as a given, placing the onus of meaning on the individual. He described it as living in a state of 'rebellion'. We can never resolve the internal conflict of faith and doubt, so let us disregard the matter entirely (but not as a gateway to nihilism! Perhaps the most appealing aspect of Camus' viewpoint is the fusion of this disavowal of a higher truth with the innate will to live, that he sees meaninglessness not as torturous but as profoundly liberating...)

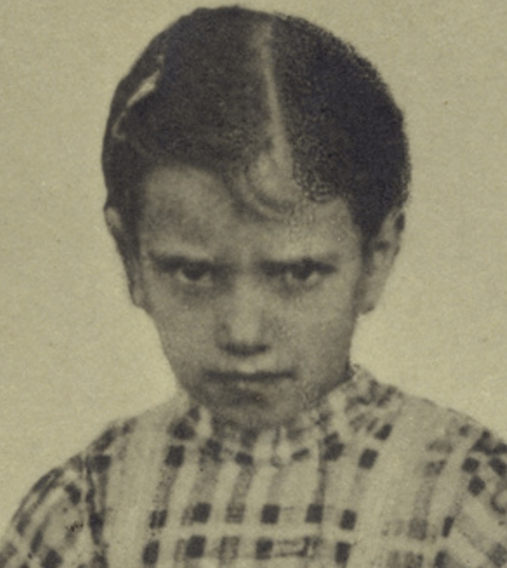

Jacinta Marto was described by her cousin as a good-hearted though overly sensitive child, prone to strops and upset. All three of them were raised in the village of Aljustrel, in homes not a five minute walk from one another, in large and devoutly Catholic families. Illiterate, the children came to know the Bible though stories Lúcia's mother would tell them. Jacinta in particular was deeply affected by tales of the crucifixion, and threats of the infernal that were used to chastise children who misbehaved. Even before the apparitions she was intensely preoccupied with sin. She would burst into tears considering the suffering Christ underwent for all the world's sinners, and the punishment awaiting those who did not recognise His sacrifice.

It is still possible to visit where they grew up, following a path from the town centre through some farmland for twenty minutes or so. The way is marked with roughly a dozen small chapels, engravings of quotes from Our Lady recounted by Lúcia in her memoirs, and a larger shrine at the site of a later visitation. The homes are small and bare buildings with low roofs; you first enter a main room, with chests of drawers and a dining table, and doors to bedrooms on all sides. Both of the houses are very dark. In Lúcia's home you can still see her crucifix, which hangs next to various photos of her as a child and in Carmelite habit. A large oil painting of Francisco and Jacinta adorns the wall of the Marto home. Some hours after attending Francis' mass, a woman who has travelled from South Africa enters the side bedroom where Francisco died and suddenly cries out, nearly collapsing onto the wooden floor.

At the first apparition, the children spoke of seeing hell suspended between her opened hands. Lúcia described the image as a “sea of fire”, filled with “demons and souls in human form, like transparent burning embers, all blackened or burnished bronze”. The Lady told the children, terrified by this momentary vision, to pray for forgiveness, to be “saved from the fire of hell” and “lead all souls to Heaven”. The vision had resembled hell in the way Lúcia's mother had often described it to them, that cave of sinners and beasts consumed by a great bonfire.

In the wake of this revelation, Jacinta lost interest in the games she had previously enjoyed playing in the pasture; she began to dedicate nearly all of her time to reflection and prayer. Of particular interest to her was the concept of eternity, that those condemned to hell never died or turned to ashes, and that those granted access to heaven never had to leave it behind. Later, confined to a Lisbon hospital bed, she remarked to the Mother Superior of a local orphanage: “What is it all for? If only they knew what eternity really was... How changed they would be, if they knew what awaited them”.

Jacinta and Francisco became dedicated to disciplined rituals of self-mortification, far more so than their cousin. They would give their lunches away to poorer families in the community and to their flocks; Jacinta would eat acorns, even forgoing those from holm-oak trees, to deliberately choose the far more bitter acorns of oaks. She would refuse water and shade to induce headaches and nausea. The three of them wrapped cords around their waists, keeping them on tightly for vast stretches of time.

Initially, the local parishioners and the children's parents did not believe their stories. After Lúcia refused to confess that she had lied before two priests, the three of them were imprisoned in the nearby town of Ourém and told they were going to be burned alive. Jacinta suffered greatly from having been abandoned by her parents; though Francisco reminded her that the pain of the experience could be offered for the conversion of sinners, Lúcia recalled that Jacinta was ultimately unable to say the Rosary in their prison cell, crying for want of her mother.

Lúcia was not always certain that her visitations were genuinely divine; it was during this period of scrutiny by the Church that she became concerned she had been deceived by a demonic apparition. She had a dream in which a laughing demon attempted to drag her into the depths of hell; awaking her mother with her screams, she spent the rest of the night wide awake from fear. A footnote in the official edition of her memoirs stresses that her doubt should not be seriously considered, it merely being the result of trying familial circumstances and the suggestion of an unconvinced local priest that she may have been misled. We should also remind ourselves of Lúcia's age at the time of the apparitions, and the susceptibility of children to pressure and persuasion from figures of authority.

Camus also had stretches of doubt with his concept of rebellion. He asserts his commitment to what is undeniable, what he absolutely cannot reject or doubt, yet still speaks frustratedly of an irrepressible “desire for unity, this longing to solve, this need for clarity and cohesion. I can refute everything in the world surrounding me that offends or enraptures me, except this chaos, this sovereign chance and this divine equivalence which springs from anarchy”. A silent universe, however self-evident, remains a dissatisfactory and restrictive resolution, a half-answer. He does not settle the question of interpretation but simply begins his investigation at a different point, identifying a foregone conclusion but still having to find the right path towards it. For those like Lúcia, those who instead have seen the universe open up to them and speak, the same dilemma exists.

Jacinta fell ill, along with her brother, a year after the first apparition, in the midst of the influenza epidemic. She continued to refuse water in the early stages of her illness, accepting milk and broth only because it hurt so much to swallow them. Francisco died at home in April 1919. Jacinta was later transferred to hospital, not long after having been visited by Our Lady and told she must go not to be cured, but to suffer further for the love of God, and then to die alone, an instruction which inflicted perhaps the deepest emotional toll.

Already thinner from fasting and penitence, her condition worsened considerably throughout the year. She developed pleurisy and an abscess in her chest cavity, and although this caused her monumental pain, it was a suffering she endured readily, later remarking to a nun that “we must be willing to suffer if we want to go to heaven”. In a further act of sacrifice, she continued to leave her bed every night to pray, despite having become so weak she could no longer push her forehead to the floor (this practise she only stopped when a priest told her it was permissible “to continue her assaults on heaven from a prone position”). When briefly home from treatment, she would continue to walk to weekday Mass, emaciated and exhausted.

Later, she returned to another hospital in Lisbon, where she died in March 1920, three weeks before her tenth birthday.

Today the Church celebrates and remembers Jacinta as a strikingly firm believer; of three exceptionally pious shepherd children, she was the most devout, the one who possessed the most resolute dedication to her convictions and to God. In the second half of her short life, she suffered monumentally – from neglect and disdain, from self-denial, from the unbearable weight of a perceived responsibility for the crimes of mankind – but never from doubt, that which even bishops of Rome, or Camus for all his empiricism, can never circumvent. This is perhaps why Francis spoke of the virtue of children during his homily: it is a combination of the depth of their imagination with the innocent smallness of their worldly experience that allows them to believe unwaveringly in the truth of what they are doing.

I often wonder what I would have said to her, given the chance. If I had been with her in Aljustrel as she gave all her food away to her flock; in the prison cell the clergy condemned her to; at her bedside as she awaited death in the hospital, and lamented how much more she could have offered. There is an implacable desire to intervene, to prevent; to say that it need not all weigh so much, that even those with the purest intentions cannot account for a world of sin. She wouldn't have listened. Children can be so tenacious, and are so easily led by the tenacity of others. Some doubt can allow us to put matters in perspective, and prevent us from acting unreasonably, lest we do harm to others or to ourselves. There is so much that we are unsure of, that we cannot help or foresee. I wish she could have known it was not her fault.